August 14, 2025

A Song of Praise for Native Grasses

Although the word “grass” probably brings to mind a broad, short, dense carpet of greenery where children play and families picnic, tallgrass and mixed prairies once dominated the landscape of North America.

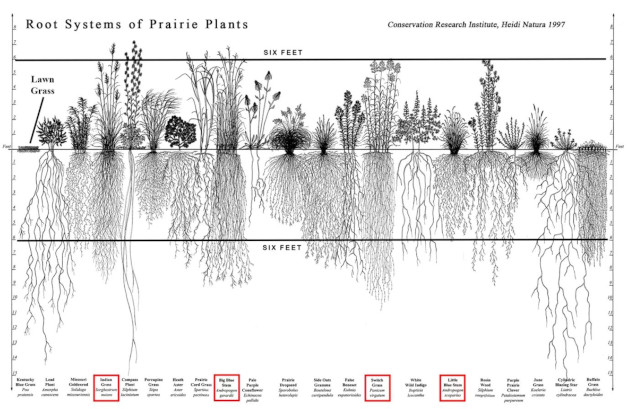

While we aren’t the biggest fans of lawn grasses, we love native grasses around here. In the native prairies and savannahs where these species originate, grasses form the backbone of the ecosystem, providing clumps of dense cover where quail can raise their young, horned lizards can hide, foliage feeds numerous native butterflies and skippers, and seeds feed birds through winter. Prairies, and the grasses that define them, also help mitigate flooding: the dense, fibrous root systems hold soil in place and absorb water like a sponge, protecting our watersheds and our homes (a subject on all of our minds after this summer’s catastrophic floods).

Above: Roots of native grasses hold down soil and absorb water exponentially better than non-native lawn grasses. Image Source: Flint Hills Tallgrasses (U.S. National Park Service)

Of course, not everyone wants–or has space for–a landscape that resembles a true prairie, where grasses form 60-70% of the abundant, diverse plant community. Even a formal landscape can benefit from both the ecological benefits and the abundant beauty that native, ornamental bunch grasses can provide.

Let’s Talk Specifics.

What native grasses will you find here–both in our nursery and out in the world?

First, let’s discuss the heavy hitters–the so-called “Big Four” grasses that form the backbone of tallgrass prairies in North America: Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), and Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium). These once-abundant native grasses dominated the landscape, co-evolving with migrating bison herds to withstand intermittent heavy grazing and prescribed burns performed by the indigenous tribes that lived alongside the buffalo.

In the last ten years, both Little Bluestem and Switchgrass have become darlings of the horticultural world, with new cultivars expressing the species’ huge potential for variety of dramatic fall color, decorative seedheads, and size. Some varieties, like “Little Red Fox,” display a compact habitat and deep red fall color. Others, like “Heavy Metal,” had the metalhead who orders our plants at hello–but it’s also really cool looking, with dramatic blue-green foliage and red growing tips.

Above: Little Bluestem is the star of late autumn hikes in Central Texas. Image source: Wildflower Center

Big Bluestem is truly a statement grass, reaching an incredible size–4’-8’ tall and wide. Until recently, its large stature has made it less popular in gardens even though it has beautiful fall color, decorative seed heads, terrific value for a wildlife or butterfly garden, and great potential as a screening or privacy plant (mixed in with giant annual sunflowers? Yass, queen. You wouldn’t have to look at your neighbor in less than one season, and the abundant layered foliage of this living screen would filter sound by a busy road really well, too). That’s why I’m really excited that we have a big bluestem cultivar in this week called “Lord Snowden,” found by John Snowden in Crawford, Texas, just a few hours north of here. Snowden selected this specimen for its varied, interesting fall colors of dusky reddish purples, pinks, copper, and even tangerine.

While Gulf Muhly, native to Southeastern Texas, has been a landscape staple for a long time thanks to its gorgeous pink seedheads in fall, we also welcome the increasing popularity of central Texas native Big Muhly. If gulf muhly seems to drown or struggle in your clay-based, rocky soil, try native big muhly, seep muhly, or deer muhly instead, all of which favor our shallow, limestone-based soils. Big muhly is truly a statement grass, occupying five cubic feet of garden space with its soft texture and feathery plumes in the fall–the perfect substitute for invasive pampas grass (which we will never carry).

Above: Big muhly makes an excellent living fence and a dramatic garden accent. Image Source: Wildflower Center

Fortunately, you don’t have to go big to incorporate native grasses in your landscape. Whether you’re looking for short, soft spots of texture or grasses to mix in with your reseeding bluebonnet patch, you can look to our native shortgrass prairies. Native Sideoats Grama provides critical habitat for horned lizards and the insects that they eat, as well as hosting several species of skipper and butterfly. It blends in beautifully with wildflowers, adding texture and interest between bouts of color, and if you say it looks like a weed, I will be very displeased with you. We also have a showy cultivar of Blue Grama called “Blonde Ambition,” selected for abundant chartreuse seedheads that it maintains throughout the winter. Blue grama is one of the most drought-tolerant native grasses, requiring only seven inches of rainfall per year, making it a popular component of wildflower mixes.

Got shade? We’ve got Inland Sea Oats. This is a perfect background plant for shady gardens, and an absolute must for rain gardens under oak trees. Like every other native grass, it hosts several species of skipper.

And, of course, if you’re hoping to create a more traditional pocket prairie by direct sowing native species or just hoping to kill your lawn and replace it with an HOA-friendly native alternative, we also carry mixes from Native American Seed: Thunderturf, Sun Turf, Caliche Mix, and native Little Bluestem. Add a wildflower mix like Butterfly Retreat and you’ve got an ecosystem ready to go.

Care and Keeping of Native Grasses

Here’s the best part–or, perhaps, the hardest part. These grasses barely need you.

Like many prairie species, native grasses get oversized, floppy, and unattractive with too much water and fertilizer. They do not want the same kind of care as the lawn grasses that share their name (and little else). Cap your sprinkler systems or switch them to drip irrigation; once established, native grasses can subsist on little or no supplemental water. Instead of fertilizing regularly, you can use a Microlife product like 6-2-4 and Super Seaweed at the time of planting, and topdress with compost once or twice a year. If your pocket prairie is in danger of mulching itself out of existence, you can clean last year’s grass leaves in late spring, add them to your compost pile, and return that to your garden once it’s done cooking. Less efficient than fire and buffalo, but more suburb-friendly.

They also do not want too much space. Native prairie plants like to crowd together, competing for root space and occupying different levels above the soil. Shorter grasses like the gramas shade the soil, and taller grasses provide cover for lizards, small birds, and caterpillars. Native grasses make great companion plants for milkweeds!

Above: Native switchgrass, planted close together and watered sparingly, makes a lovely backdrop for colorful Rock Penstemon in this bed designed by staff horticulturist Linden Hickson.

Above: Native switchgrass, planted close together and watered sparingly, makes a lovely backdrop for colorful Rock Penstemon in this bed designed by staff horticulturist Linden Hickson.

If you’re considering using a rain garden to manage stormwater runoff on your property, native grasses are invaluable. Plant them along your constructed dry creek bed to help filter out debris from your roof and keep this landscape feature from being washed away, and include them in the rain garden itself, too, where their roots will suck water down long before standing water can form.